Loading map...

A noteworthy soundscape[1] can be found on the soccer field in south campus Pomona. The grass field, sunken into a semi-bowl and ringed by trees, is removed from the din of quotidian campus life, but nonetheless contains its own sonic information. During a game, regardless of the fan turnout, the field is filled with a constant cacophony, at first seeming chaotic and at times frenetic. However, there is direction and meaning behind each sound, as is true with any soundscape. Potentially the most salient acoustic feature of the game are the shouts of encouragement, instruction and occasional scolding that ring out from a majority of the players and coaches on and off the field. Though they might seem overwhelming, each shout carries with it its own purpose, a communication that connects each player on the field to each other by solidifying team shape and organization and creating a psychological connection. This can only truly be appreciated by those who know the sport, as defensive or offensive tactics may not be intuitive, but rely on prior knowledge of the listener.

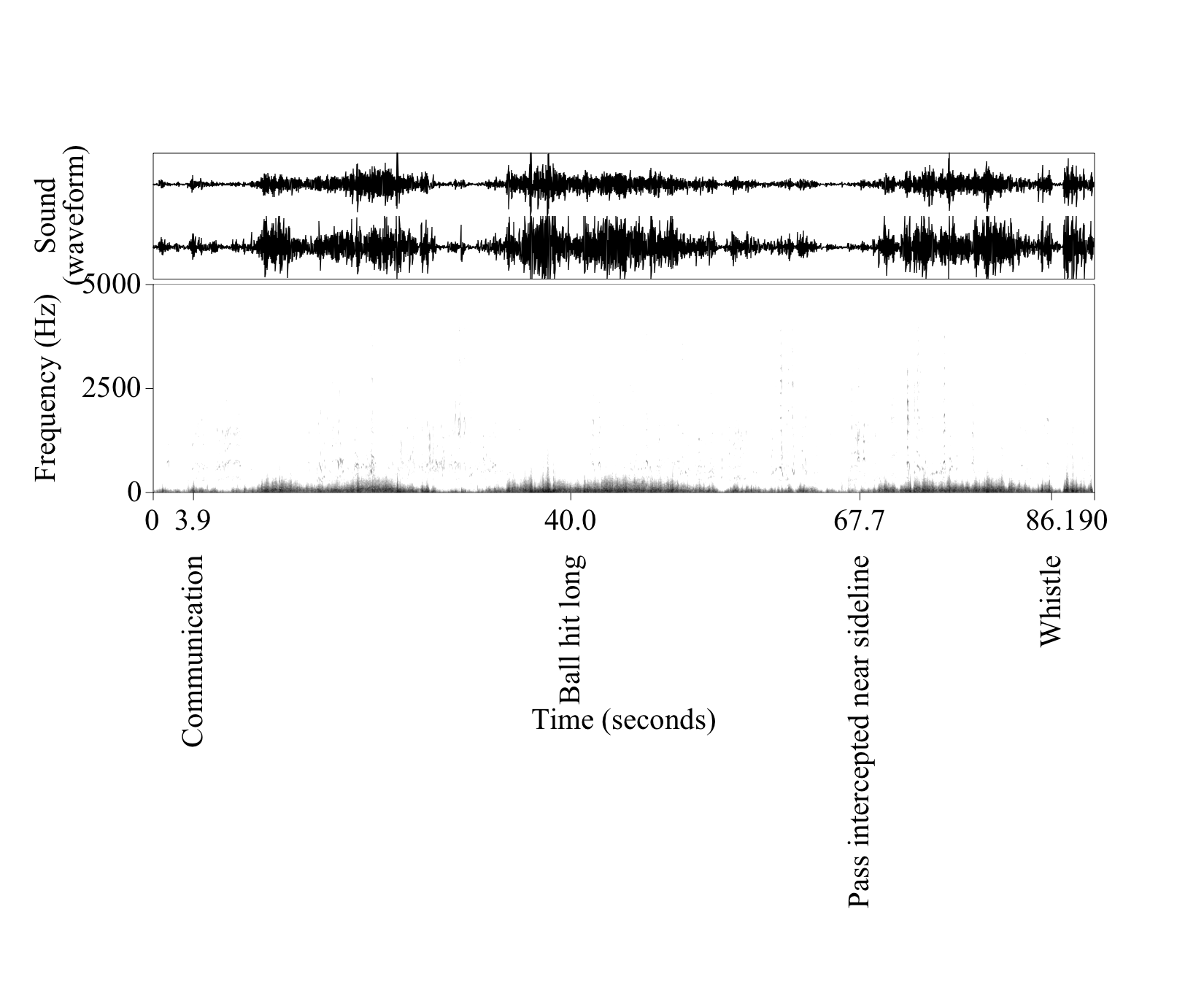

However, not all sounds on the field require their own context. Sounds of the referee’s whistle, or rises and falls of pitch that players communicate with imbue certain intuitive meanings. These signal sounds[2] convey meaning to the listener despite the listener’s knowledge of the sport. The whistle, for example, carries an inherent significance of warning, and therefore is recognizable and deconstructable by any listener. The change in intensity of the whistle (86.1s) can provide the listener with a sense of the severity of the infraction, while the rise and fall of the shouts of the crowd or players can convey the emotional reaction to the event.

In addition to these knowledge-dependent and signal sounds there are some moments in the game with archetypal qualities[3], specifically in the moment before a long pass, or between a shot on goal and the subsequent goal. There is a moment, between the movement of the leg back and the ball forward, in which most shouting is ceased, no instruction commands the soundscape, and silence dominates. It is a moment like the moment between inhalation and exhalation, a pause before a rapid and inevitable outcome.

As in many soundscapes, there is always information and meaning to be gleaned, but often it is left unrecognized.

As is the case with any recording, this is merely a representation of the soundscape. Therefore factors like wind noise appear more salient in the recording than in the actual soundscape.

[1] The term “soundscape” is discussed by Emily Thompson, “Sound Modernity and History” (Cambridge, Mass: MIT University Press 2002) who argues that a soundscape is an “auditory or aural landscape”, making it both “a physical environment and a way of perceiving that environment”.

[2] The term “signal” to describe a certain sound in a soundscape was coined by R. Murray Schafer, “The Soundscape”, reprinted in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 101. Schafer describes a signal as a sound that must be listened to “consciously”, like that of a “whistle or bell”.

[3] The term “archetype” in the description of a feature in a soundscape is provided by R. Murray Schafer, “The Soundscape”, reprinted in The Sound Studies Reader, ed. Jonathan Sterne (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 100. Schafer describes archetypal sounds as sounds which we recognize from “remote antiquity or prehistory”, calling on a collective memory that conveys collective, deep significance.