Loading map...

Location. The walkway is wide, with a few trees, picnic tables, and small lawn spaces flanking both sides (in front of the dormitories). Small, unpaved pathways branch off the main walkway and lead to the entrances of each dormitory. The area is usually occupied by any number of students; however, because the recording was taken at a later time of night, the area and its soundscape have a fairly subdued quality. Beyond the stretch between the two dormitories, the area surrounding the walkway is generally open.

About the soundscape. The description provided below was written to reflect a Friday night during a heatwave in early September, while the present clip was recorded on a Sunday night in mid-October. I’ve chosen to keep the unaltered description here because this temporal juxtaposition reflects both the dynamism and thematic continuity of the soundscape. Listen, and compare.

—–

The walkway that spans the distance between Pomona’s Frary dining hall and College Way road is a central feature of Pomona’s landscape. Situated between Walker and Clark V dormitories, where upperclassmen traditionally live, it lies at the heart of North campus. Being the main means of access to academic buildings, dormitories, and the dining hall, this walkway is usually occupied by any number of people. It’s normally a fairly subdued area, aside from passing conversation and the bell tower that chimes every hour. However, the atmosphere varies greatly depending on time and day. The soundscape I will describe here begins at around 10:30 pm on a Friday night, outside Walker dormitory.

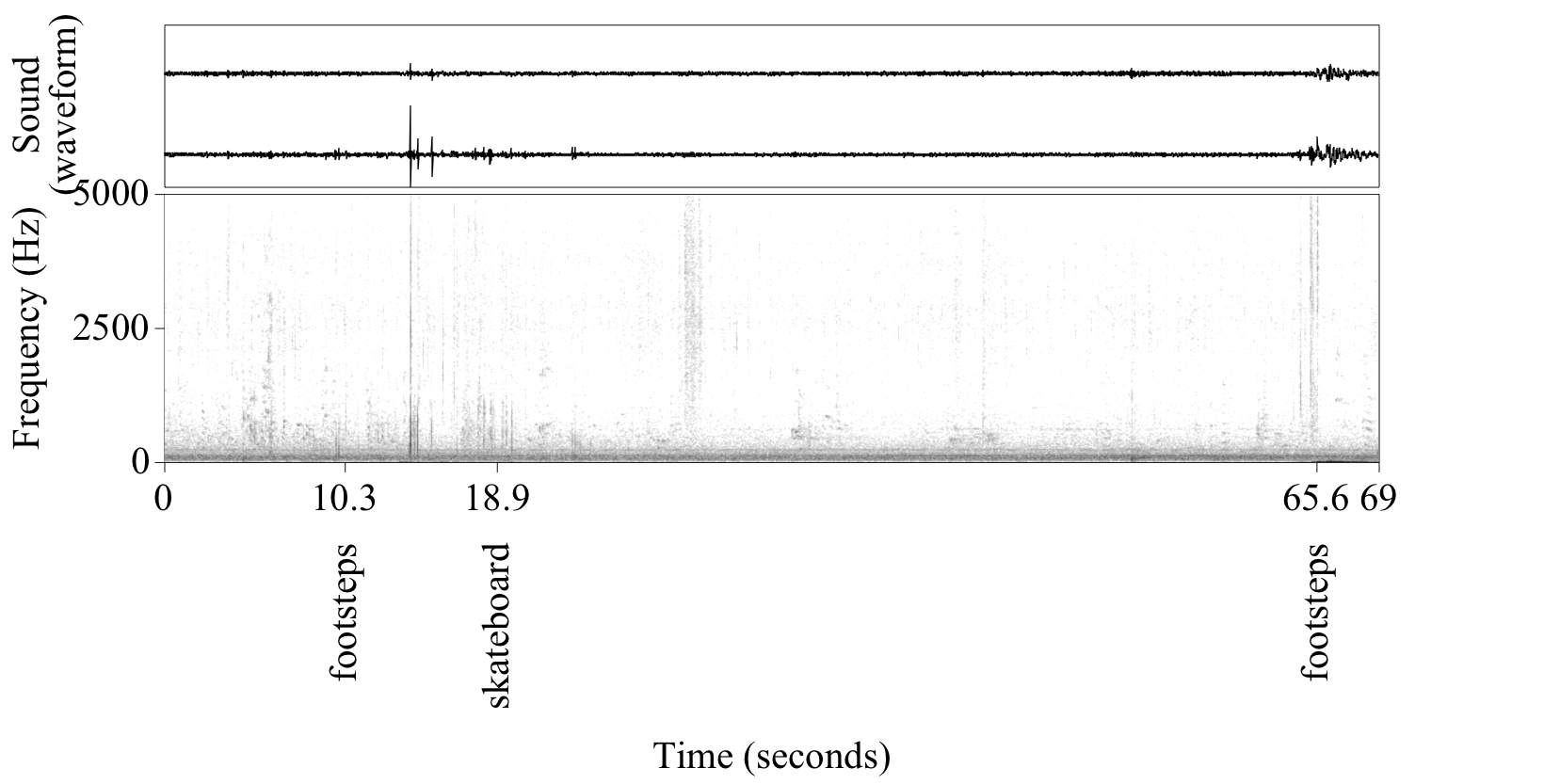

The whirr of fans turned to the highest setting emanates from open dorm windows, mixing with the muted rustle of leaves in a faint wind and the hum of distant cars. Subdued music can be heard, most likely leaking from an open window. Window blinds are clicking softly in the wind. These sounds comprise the keynotes[1] of the soundscape; they disappear from consciousness unless one actively listens for them, and yet are indispensable to the soundscape as a whole. The occasional buzzing of an airplane overhead and faint splashing from the Bosbyshell Fountain the in front of the dining hall are a step up in salience, but fall into more or less the same category. An occasional train horn blares in the far distance, and every once and a while a passing skateboard rumbles by on the sidewalk—noticeable, but not demanding attention.

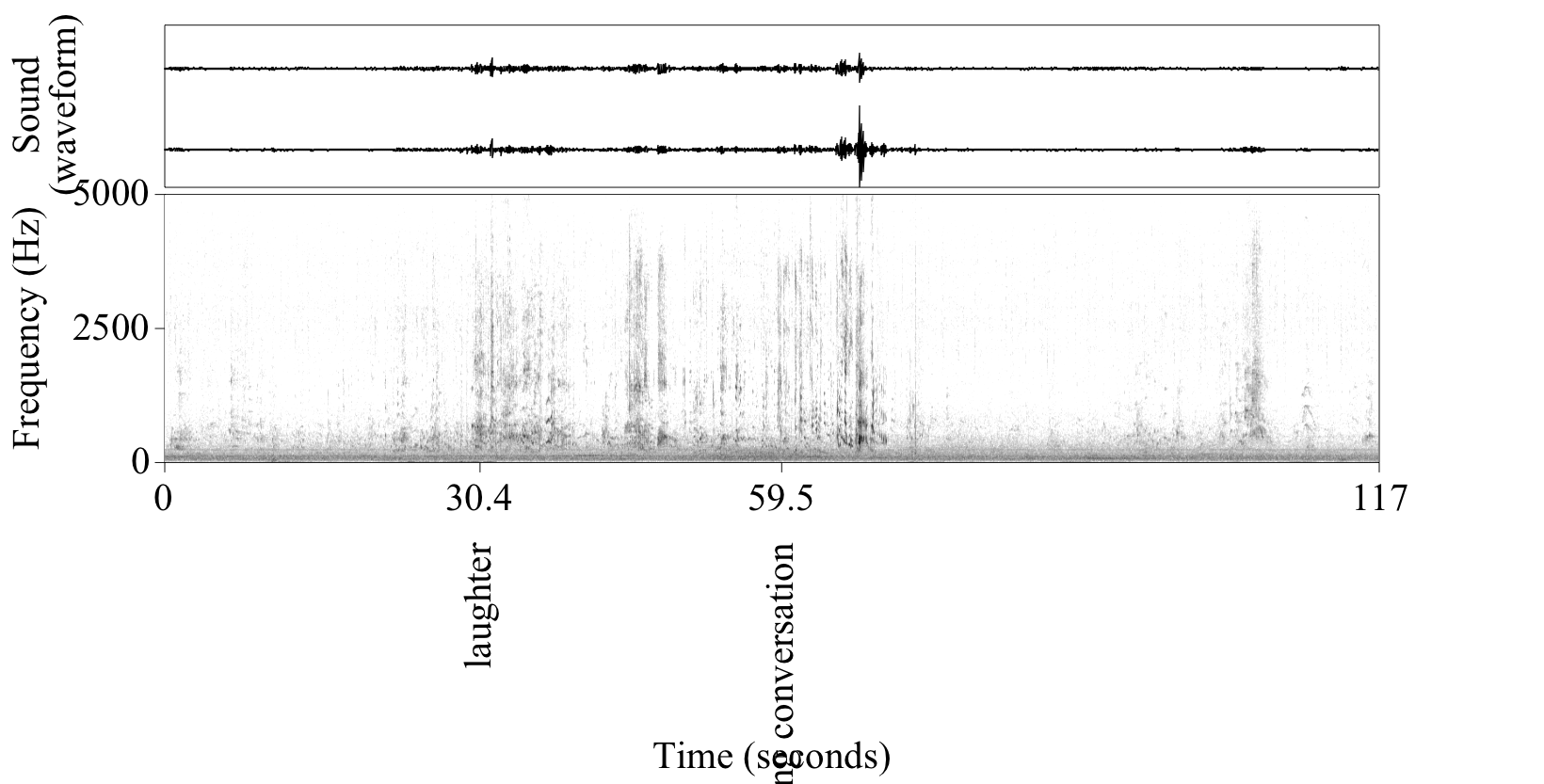

The most distinctive aspect of this soundscape, however, is not the characteristic sounds of a still night. It’s a Friday; at 10:30, groups of people are beginning to appear on the walkway, on their way to a party or perhaps just walking around. Loud conversations and laughter come and go in the sonic foreground as people pass by, the sounds apparently amplified by the concrete sidewalk and buildings on either side. These signal[2] noises evolve as the as the night progresses, and the soundscape with them. As people begin to head back for the night, their voices become slurred and inflected, and laughter rings louder—clear evidence of some form of intoxication. Every once and a while, a passing group will sing off-key to the cheers of others, or even walk up to the entrance of Frary just to hear their voices reverberate. As the night gets older, the soundscape evolves again; the number of people thin, and with them so does their laughter and cheerful conversations. The atmosphere equilibrates, eventually returning to the cool color of a quiet night.

[1]The term “keynote” as used in this context was coined by R. Murray Shafer in “The Soundscape,” reprinted in The Sound Studies Reader, edited by Jonathan Sterne (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 95–103. Shafer describes a keynote as the “fundamental tone” of a soundscape which “[does] not have to be listened to consciously… [and is] overheard but not overlooked.”

[2]The term “signal” as used in this context was introduced in R. Murray Shafer’s “The Soundscape,” reprinted in The Sound Studies Reader, edited by Jonathan Sterne (London and New York: Routledge, 2012), 95–103. Signals are, as Shafer puts it, “foreground sounds that are listened to consciously,” which thereby convey some message or meaning to the listener.